Where Are Our Raphael Lemkins !

By Subhash Gatade

20 November, 2007

Countercurrents.org

For If I Shall Not Burn

And You Shall Not Burn

If We Shall Not Burn

Then Who Will Dispel The Dark

- Nazim Hikmet

I

Whether anybody is familiar with a place called Auschwitz which is around 270 kms. from Warsaw, capital of Poland. It has been more than sixty years ago that the brick kiln structure there which housed detainees witnessed silent sufferings of lakhs of people who were put to death in myriad ways by the henchmen of Hitler.

A majority of the victims were just put inside a gas chamber where they died immediate death after inhaling a poisonous gas like cynaide. Or many of them were literally choked to death or starved to death. Quite a few of the detainees died because of intense hard labour and malnutrition.

Looking back we know that the killings were no spontaneous action on the part of the Nazis, Hitler in his autobiography 'Mein Kampf' had specifically talked of 'submitting twelve to fifteen thousand of these Jews who were corrupting the nation' to be '.. forced to submit to poison-gas'.

The recent revealations in the Tehelka expose of the Gujarat carnage in the year 2002 vividly brought back to' life' the deaths of 11 lakhs people in Aushwitz. One could easily draw a parallel between the likes of Rudolf Hoess, Dr Joseph Mengel, Dr Clark Clauberg. Arthur Libenatial, Richard Baer and the likes of Dr Praveen Togadia, Dr Maya Kodnani, Dhimant Patel, Jaideep Patel, Babu Bajrangi, Haresh Bhatt, Anil Patel and to top it all Herr Modi..

History bears witness to the weird 'scientific' experiments conducted by the likes of Dr Joseph Mengle on the detainees where caustic chemicals were injected in the bodies of women to test a new series of contraceptives.Perhaps the perpetrators of Gujarat carnage were no less 'innovative'. If the Germans had devised special gas chambers for the hapless Jews and many dissidents of the Nazi regime, the likes of Babu Bajrangi turned a sewer line into a gas chamber by just putting a big boulder on a sewer line where a group of Muslims were hiding from the marauders of the Hindutva brigade. Only their dead bodies could be recovered from the pit after a few days. If the Nazis use to put the detainees in a small pit with little source of oxygen where they used to die for want of oxygen, the followers of Modi-Togadia managed to drop oil on their hapless victims who were hiding in a pit and burn them alive. Babu Bajrangi, the main perpetrator of the Naroda Patiya massacre, a leading Bajrang Dal/VHP figure, explaining his 'heroism' during those killings, naratted an incident how '.they were clinging to each other in the pit. Then we threw in oil and burning tyres and killed them'. One could just go on drawing one's attention to the similarities and the dissimilarities in the Aushwitz experiment and the one Genocide which all of us witnessed before our own eyes - thanks to the 24 hour news channels beaming out 'war' or 'riots' live into our homes.

It is now history how the humanity tried to exorcise itself of Auschwitz and the ghost of Nazism and Fascism. The historic Nuremberg trials gave its final verdict on the Nazi criminals. Leading perpetrators of Auschwitz were sent to gallows in front of Aushwitz itself. Rudolf Hoess who led the Auschwitz camp for full three years and who gave graphic presentation of the working of Auschwitz in his memoirs and described it in detail before the court also was the first to be hanged.

Perhaps it is a sign of changed times or the slackening of the resolve of humanity that today sixty years after Auschwitz the 'Neros' of Gujarat have been allowed to go scot free. Forget punishment, these perpetrators of ghastly killings, - the strategists, the planners and the actual footsoldiers - are today a respectable lot. All those people who have accepted their crimes before camera about the planning that went in making the genocide happen and the role played by them in burning down houses,killing innocent people or raping innocent girls/women have been allowed to go scot free. If the victories of their political masters over the dead bodies of thousands of people in a 'democratic' process was hailed as the 'vindication of their succesful experiment' last time, if they receive an encore in a similar exercise in coming days then it would further legitimise their crimes against humanity.

A question naturally arises whether every sensitive, humane, justice loving person / formation on this part of the earth is ready to take this further humiliation with folded hands or is ready to break asunder the carefullly maintained conspiracy of silence. Would it be correct on our part to hold the carnage as an act of few 'psychotic killers', a 'product of few crooked minds' and leaving the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its affiliated organisations - who planned and executed it - intact ? Would it be correct on our part to accept the fictious division between 'Hindutva' and 'Moditva' and reserve our scorn for Narendra 'Milosevic' Modi alone or keeping ourselves focussed on the dangers of majoritarianism in a multireligious/ multicultural country like ours ?

II.

At the beginning of the Great War, or even during the War, if twelve or fifteen thousand of these Jews who were corrupting the nation had been forced to submit to poison-gas…then the millions of sacrifices made at the front would not have been in vain.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Campf ( My Struggle)

The year 1933 saw an interesting presentation by a Polish-Jewish scholar Raphael Lemkin in a legal conference held under the auspices of League of Nations ( a precursor to the United Nations ) at Madrid. This gentleman who had closely studied the massacre of Armenians in Turkey during first world war or the genocide of Assyrians in Iraq the same year and the manner in which all such crimes against humanity went unpunished made a novel suggestion in his paper 'Crime of Barbarity'. According to him all such crimes against humanity which take the form of killing of innocent people merely because they belong to particular community, region, ethnicity etc should be considered crimes under international law.

It was expected that the imperial countries who were themselves cosying up to the Nazi and Fascist regime in Germany and Italy did not find any merit in Lemkin's argument. And his own government which had established good rapport with the Nazis by then also disapproved of his suggestions.A few of his comments at the Madrid Conference so infuriated the Polish government that the Polish Foreign Minister asked him to resign from his job as Public Prosecutor and as teacher in a college.

Of course, very few people realised then that it was an idea whose time had come. The beginning of the genocidal Second World War and the establishment of concentration camps like Auschwitz and the persecution of particular communities under the Nazi dispensation further pushed humanity to do something concrete to avoid such genocides in future.

The year 1944 saw publication of Lemkin's magnum opus 'Axis Rule In Occupied Europe' getting published in US. The book comprised of detailed legal analysis of Nazi rule in World War II in occupied countries. Lemkin further concretised his ideas of Genocide as an offence against international law.

The international community did not find much difficulty in accepting Lemkin's ideas now and it formed the legal basis of the historic Nuremberg Trials which were held against the Nazi leaders who 'conducted deliberate and systematic genocide - namely, the extermination of racial and national groups.' The year 1948 saw the adoption of a Convention by the international community in the form of Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide by the UN General Assembly ( 9 th December 1948) which came into effect on 12 January 1951. This contained an internationally-recognized definition of genocide which was incorporated into the national criminal legislation of many countries, and was also adopted by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). The Convention (in article 2) defines genocide as:

...any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

III.

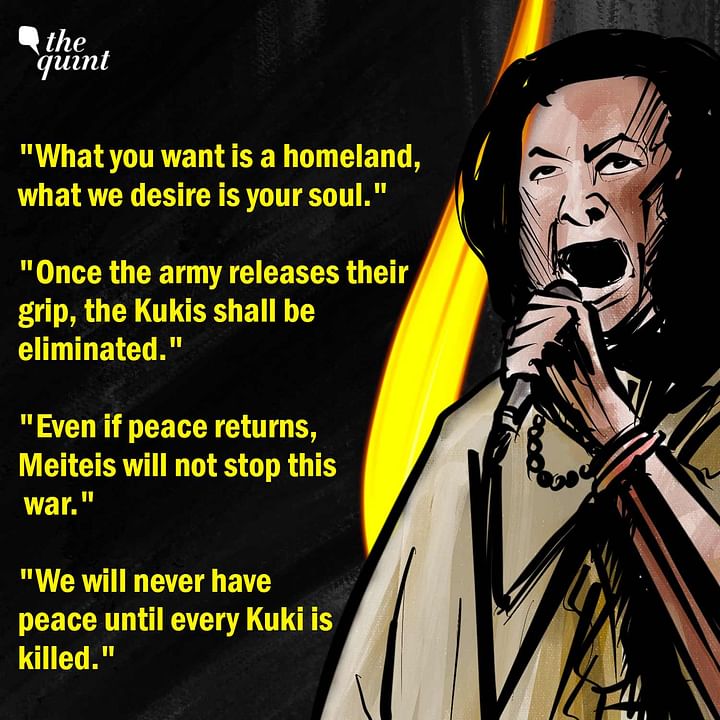

After killing them, I felt Like Maharana Pratap ......

- Babu Bajrangi, Bajrang Dal leader

As the CM, Narendra Modi couldn't say 'Kill at the Muslims'... I could say it because I was from the VHP

- Rajendra Vyas, VHP leader, Ahmedabad

Put lathis aside and pick up AK-56s, if you are to develop Hinduism. It is clear who the enemies are, Muslims and Christians

- Dhimant Bhatt, Chief Auditor of M.S. University, Vadodara

DCP Gadvi promised VHP's Kalupur zila mantri Ramesh Dave that he would kill "at least four-five Muslims" if Dave pointed them out to him. Dave took him to a house from where a group of Muslims could be seen. "Before we knew it, he'd killed five people." Dave said

- Quoted in 'Tehelka'

Any sensible person who has browsed through the sting operation done by Tehelka or who has seen its telecast on few channels would confirm that there was nothing spontaneous about the carnage which occurred in Gujarat which officially saw deaths of more than 1,000 people.

The sting operation done by a young journalist Ashish Khetan, over a period of six months, wherein he managed to talk to many ringleaders of the RSS-BJP-VHP who spearheaded the carnage about their role in the events, is definitely the 'the most important story of our time'. Ashish Khetan and the Team Tehelka need to be given kudos for the marvellous job done to persuade the 'killers' speak themselves.

Every sane person would agree with Tarun Tejpal about three particularly disturbing things about Gujarat 2002. 'The first that the genocidal killings took place in the heart of urban India in an era of saturation of media coverage' , 'The second that the men who presided over the carnage were soon after elected to power not despite their crimes but because of them' and 'the fact that there continues to be no trace of remorse, no sign of penitence for the blood-on-the hands'.

The 'sting operation' makes it clear that right from giving green signal to the Sangh workers to start an attack on the Muslims to the planning that went in making it happen the top bosses of Sangh Parivar were involved at every level. In fact they met and strategised about every aspect of the attack carefully. To shield the attackers from the law, they even consulted prominent lawyers as well as senior police officers.All sorts of weapons - from bombs to guns to trishuls - were either manufactured by the Sangh workers or were smuggled through Sangh channels from all over India. BJP's MLA from Gujarat even managed to manufacture rocket launchers in his factory. Its other contacts in the quarrying area managed to manufacture other explosives also. Since 'cremation is considered un-Islamic' Fire was the 'most favoured weapon in the rioters hand'.

But it is a sign of our changed times that neither the Congress nor other Secular parties nor the Highest court of the country who otherwise becomes hyperactive on flimsy issues deemed it necessary to go in for either 'prosecuting Narendra Modi' or 'go in for arresting the bloodthirsty criminals who had the audacity of sharing their exploits during the genocide without any sign of remorse'.

A question that naturally arise is that why did not the people in power decided to act despite clearcut evidence before them about the complicity of the Hindutva goons behind the carnage. The foremost reason seems to be the electoral considerations where the 'secular parties' wanted to forestall any attempt on part of Modi to further polarise the voters on communal lines. Apart from their own gameplan, the muted reaction on the part of the articulate sections of our society must have guided their consideration.

A few of the doubting Thomases even raised the issue of the 'timing' of the exposure and its likely impact on the electoral (mis) fortunes of the parties involved.

Perhaps some may argue that despite India signing the UN Convention on Genocide way back in 1959 it has failed to comply with international legal norms, by formulating a suitable domestic legislation.Thus the absence of domestic legislation to not only prevent and punish genocide, but also designate a tribunal for the trial of those charged has helped create a strange situation where the ability of the Indian criminal justice system to dispense justice - when it comes to mass crimes - seems to be in grave doubt.

IV

How many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry ?

How many deaths will it take till he knows

That too many people have died ?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind,

The answer is blowing in the wind

- Bob Dylan, Blowing in the Wind

There are very many ways in which India is presented and projected to the outside world. For some it happens to be the biggest democracy in the world, while for others it is one of the fastest growing economies of the world, which has now 'arrived'. Many talk about its becoming the new superpower with the demise of the yankees from the world scene.

But rarely does anyone talks about its being a 'land of mass crimes' where the perpetrators of such crimes have always gone unpunished. None of the opinion makers talk about the unholy alliance between politicos, mafiosi and the law and order machinery which has emerged down the years where the art of 'invisibilising mass crimes' is being perfected. And the target of such mass crimes are - mainly the religious minorities or people on the lowest rung of social matrix or the toiling masses of the country.

Would anyone believe that the 'first' massacre of around fourty Dalits -mainly women and children - in independent India at Kizzhevanamani (Tamilnadu, 1969) by the local uppercaste landlords went unpunished with a specious argument on part of the judiciary that ' these are upper caste people and it is impossible to believe that they would have gone walking to the dalit hamlett'. It is a wellknown fact that the dalits and other toiling masses of the area had started a strike for better wages under the leadership of the Communist Party.

Would anyone believe that Delhi, capital of the great democracy called India, was witness to the killings of around 3,000 innocents ( mainly Sikhs) merely 23 years ago and today, ten enquiry commissions and three special courts later, merely three people have been found guilty of killing the hapless 3,000 Sikhs.

Even a cursory glance at the 60 year old history of post-independent India makes it clear that neither the killing of around 40 dalit women and children in Kizzhewanamani ( Tamilnadu, 1969) nor the massacre of around thousand plus Muslims in Nelli ( Assam 1983) ; neither the genocide of 3,000 Sikhs in Delhi ( 1984) nor the cold blooded murder of 42 Muslims in Hashimpura ( UP, 1986) ; neither the killling of around 1,800 people ( majority of them Muslims, Bombay 1992) nor the massacre of scores of Dalits in Kumher ( 1993, Rajasthan) ; have been punished till date.

It would also enlighten you about the manner in which such mass crimes are rationalised or legitimised by the powers that be where a Prime Minister of a country has no qualms in commenting after massive carnage of capital's Sikh community led by his own party people that "When a big tree falls, the earth shakes". Or the chief minister of a state shamelessly discovers Newtonian 'action-reaction' thesis to cover up crimes of his own Parivar people.

Intellectuals who are quite enamoured about the tolerance inherent in 'our great culture' and the sense of inclusiveness would rather be shellshocked to find that how the ordinary, peaceloving people themselves are ready to 'metamorphose overnight' into murderers and rapists of their own neighbours on a small pretext. All the orgy of violence and their 'joyous participation' in it is then followed by a conspiracy of silence where nobody is then ready to talk the truth. Bhagalpur in Bihar which had become such a site of violence where officially over a thousand people had been slain, most of them Muslims, is still remembered for a particular incident. In Logain village, 116 Muslims were massacred, buried in a field and cauliflowers grown over their bodies.

The scenario needs to be drastically changed if India wants to emerge as humane society. It is a challenge before everyone of us. If people of the subcontinent resolve that 'the biggest democracy on the face of the earth' should not henceforth be remembered as a 'land of mass crimes' then it can happen soon.

Times are such that this simple proposal may appear utopian to a large cross-section of people. But there is no other alternative than to persist in one's attempt at individual as well as collective level, to unleash processes and strengthen institutions so that it could be expedited.

As mentioned above it was the year 1933 when a Polish-Jewish scholar called Raphael Lemkin first thought of this idea. We are also told that at a personal level Lemkin faced tremendous tragedy. He lost 49 relatives in the holocaust who were among the 3 million Polish Jews who were killed during the Nazi occupation. But all such personal tragedies did not deter him from continuing his work to convince humanity.

Where are OUR RAPHAEL LEMKINS who can yell IT'S ENOUGH !