In 2018, the 1992 test

Many of those charged in the Babri Masjid demolition case are lawmakers. That’s what makes the case a litmus test for rule of law in the country

Written by Seema Chishti

|

Updated: June 30, 2018 1:19:45 pm

In May last year, a special CBI court charged the 12 accused in the

Babri Masjid demolition case of criminal conspiracy under Section 120B

of the Indian Penal Code.

In July, the Supreme Court will resume hearings to the title suit of

the land in Ayodhya. But it is another litigation, related to the

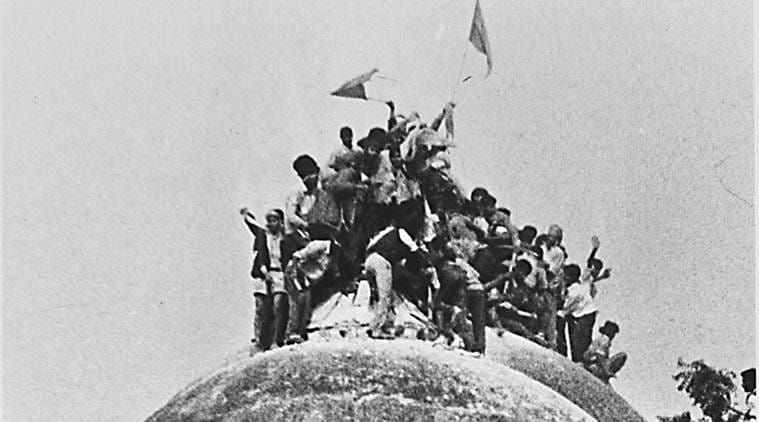

demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, which holds great significance

for India as a constitutional republic. The verdict in this case could

send out the powerful message that the law applies equally to everyone.

Or indicate that it is soft on those in power.

In May last year, a special CBI court charged the 12 accused in the

Babri Masjid demolition case of criminal conspiracy under Section 120B

of the Indian Penal Code.

In July, the Supreme Court will resume hearings to the title suit of

the land in Ayodhya. But it is another litigation, related to the

demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, which holds great significance

for India as a constitutional republic. The verdict in this case could

send out the powerful message that the law applies equally to everyone.

Or indicate that it is soft on those in power.In May last year, a special CBI court charged the 12 accused in the Babri Masjid demolition case of criminal conspiracy under Section 120B of the Indian Penal Code, to be read with sections 153, 153A, 295, 295A and 505. These charges include conspiracy, spreading animosity between specific groups and provocation with intent to cause riots, among other things. The special court is hearing the matter in Lucknow. Significantly, those accused of exhorting people to bring the mosque down — or at least being apparently happy about its demolition and the subsequent events — are now making laws. This is what makes the Babri Masjid demolition case more important than ever.

On June 25, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath took special care to attend functions involving the contested land at Ayodhya. He said there was “no doubt” that the Ram temple will be built. Ram Vilas Vedanti — a member of the Ramjanambhoomi Nyas also present at the function — referred to the Babri Masjid demolition and said “just like everything happened then without court orders. before the 2019 elections, the construction of the temple would start in Ayodhya. I assure you”. Uma Bharti, Union minister charge-sheeted in the case said, a day later, she expects “a bold step” would be taken towards building the temple because Narendra Modi is at the helm at the Centre and Adityanath is leading the UP government.

Two other important accused in the case, LK Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi (both former Union ministers and BJP presidents) have been pushed into retirement — for entirely secular reasons — but they remain symbols of the country’s most powerful party in 30 years. Kalyan Singh, a governor now, was the chief minister on whose watch the masjid was torn down between noon and 5.30 pm on December 6, 1992.

When the BJP led the ruling coalition from 1998 to 2004, the Ayodhya issue — along with Article 370 and the Uniform Civil Code — was put on the back-burner. The party had to give in to the exigencies of coalition politics. The broad idea was that these demands stood outside the pale of the law.

A leadership that emerged during the Emergency became the establishment in 1970s. The Mandal issue threw up the country’s leaders in the Nineties. The leadership that grew out of the disruption centred around the Babri Masjid disruption now holds office at the Centre — and enjoys an absolute majority.

Uma Bharti, Kalyan Singh, LK Advani, MM Joshi, all charged with having led or participated in the assault on the Babri Masjid, are members of the ruling party. Adityanath’s politics drew from the Ayodhya divide of 1992. In their book, Everyday Communalism, researchers Sudha Pai and Sajjan Kumar note that there were 28 FIRs against Adityanath and his Hindu Yuva Vahini in the wake of the Gorakhpur riots. How these and other cases were quashed with him as the chief minister is another story.

There are many principled arguments about the damage that is inflicted on democracy when the fringe becomes the law. But the matter is also germane to a basic question centred around the rule of law — how it deals with the politically powerful.

The World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Rating speaks of the primacy of the “regulatory environment” and lays stress on fidelity while “enforcing contracts”. But how can the country be seen to be upholding regulatory norms if the bare basics of the rule of law aren’t asserted loudly and clearly?

So, even if those charged with the destruction of the Babri Masjid have the popular mandate, the law must act against them if they are found guilty in a criminal case. How India acts in 2018 with respect to what happened in 1992 is an important test for its democracy.