‘Historic hurt’ is a modern phrase. Muslims were integral to South Indian gods

The legends of Vavar and other South Indian gods venerated by both Hindus and Muslims show that the Deccan's religious history in the region is far more complex.

Every year, millions of devotees congregate at the gold-plated shrine of the Hindu god Ayyappa in the Sabarimala temple in Kerala. Thousands undertake an arduous forest trek of over 60 kilometres to reach there. Of those, many start from the town of Erumely where they perform an ecstatic dance; they break coconuts and offer them, along with pepper and rice, to the god. They do all this on the premises of a grand mosque of Vavar Swami, a Muslim saint believed to have lived between the 9th and the 14th century, joined by Muslim devotees of Ayyappa. After arriving at Sabarimala, they also pay their respects to Vavar in a shrine at the foot of the Ayyappa temple itself.

Today, both Hindu and Muslim devotees believe that they must take Vavar’s permission before worshipping Ayyappa since the former was his devotee or companion. Some claim that this tradition is a way of assuring good relations between religious communities. But exploring the legends of Vavar, and other South Indian deities venerated by both Hindus and Muslims reveals that the history of religious interactions in the region is much more complex and fascinating.

Marriage, ritual, and social hierarchy

Ayyappa is just one among many Hindu deities to have a Muslim companion (using the term ‘Hindu’ to refer to such diverse gods is, it should be noted, a colonial invention). In medieval South India, even the most elite temples integrated Muslims into their mythologies and worship. At a time when Ayyappa at Sabarimala was a relatively minor god with worshippers only from the Travancore and Cochin regions, Ranganatha at Srirangam and Venkateswara at Tirumala already attracted royal patrons and endowments from hundreds of kilometres away. Each of these gods is believed to have married a Muslim princess devoted to him: Thulukka Nachiyar and Bibi Nancharamma, respectively. The worship of these goddesses continues to this day and is a part of the temples’ annual ritual calendar.

Perhaps the most interesting example of this phenomenon is in the legends of a Deccan pastoralist god known as Mallanna in Telangana, Mailar in Karnataka, and Khandoba in Maharashtra. Elite worshippers believe that he is a form of Shiva, but he is primarily a god of the ‘lower’ castes and migratory peoples. His myths are astonishingly vibrant, incorporating influences from many different communities and traditions.

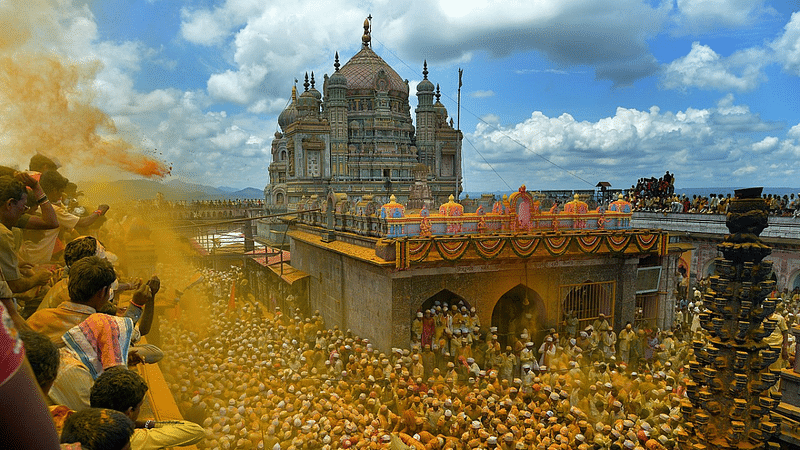

At Jejuri, Khandoba’s largest centre, he is believed to have five wives. G.D. Sontheimer, an expert on Indian folk traditions, lists them in Criminal Gods and Demon Devotees: “Mhalsa, a Lingayat; Banai, a Dhangar shepherdess; Phulai Malin, from the gardener caste; Rambhai Simpin, the tailor woman; and Candai Bhagvani, a Muslim woman”. Candai is believed to have been from the oil-presser caste. Oral epics relate stories of these wives and their arguments (and reconciliations) over ritual purity. One refrain, documented by Sontheimer, goes: “Banu (Banai) and Mhalsa are of different castes, [but] for the god Mallari (Khandoba), they eat from the same plate.” In one of his legends, the god even visits Mecca to obtain sacred turmeric for a future wife — and introduces its denizens to biryani!

Muslims also play important roles in the rituals of Khandoba. On Somvati Amavasya days, he is carried in a palanquin for a hunting expedition; the procession is led by a Muslim who attends to the god’s horse. A Muslim is also traditionally Khandoba’s policeman and the guardian of his stables at Jejuri. Muslims call the god Mallu Khan or Ajmat Khan, and he may be depicted as a Pathan on horseback. The fact that Mallu Khan is the same as Shiva can be seen in an inscription dated 1703 from Epigraphia IndoMoslemica (page 20): “śrī guruliṅga jaṅgama vibhūtarudraksha-bhūsena sadāśiva śaṅkara śambhu mahādeva mahārudra maluskhan”. Epithets usually applied to Shiva — Shankara, Shambhu, Mahadeva and Rudra — are used also for Mallu Khan.

Interestingly, we also see the converse of this phenomenon, where communities we think of as ‘Hindu’ venerate Muslim figures. The most noticeable example of this is Peerla Panduga (‘the festival of the Sufi Pirs’), an annual Muharram celebration in Telangana where ‘lower’ castes participate in processions and worship at dargahs.

What all these reveal is that in popular worship, sacred figures offer a space where local groups signal their places in the community — hence, Khandoba’s wives, each of a different caste, play a specific role in his rituals. It is not simply a matter of religious tolerance but rather a sign that local traditions and social hierarchies transcended religion. Deities like Thulukka Nachiyar and Nancharamma, as princesses, were a node for elite Muslims to patronise and participate in the worship of royal gods. Similarly, writes Dominique-Sila Khan in Lines in Water: Religious Boundaries in South Asia, Candai Bhagvani and Vavar Swami show that Muslims from working-class backgrounds actively participated in local traditions, often through legends that one of their own was a companion of a god. Yet another example of this phenomenon is Muttal Ravuttan, a Muslim who acts as the bodyguard of Draupadi, the wife of the Pandavas and a popular mother goddess in rural Tamil Nadu.

Also read: South India challenges the notions of medieval Islam—lessons from Deccan history

Religious Identities: A line in water

Today, occasional examples of Indian Muslim kings attacking temples are portrayed as ‘proof’ that relations between Islam and Hinduism have always been driven by hate and intolerance. But the truth is that temple destruction was not always seen as hatred towards Hindus even by Hindus. If that were really the case, we would certainly not see local ‘Hindu’ communities such as Khandoba, Ayyappa and Draupadi worshippers actively incorporating Muslim occupational groups.

Elite violence did not get in the way of daily life until 20th-century nationalism projected its own anxieties into the past. After all, the Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana claims (Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume 5, Hassan District no. 53) that he left so many Tamilians’ skulls alongside the Kaveri river that they stopped the flow of the southern winds. Yet, medieval Tamils did not hold all Kannadigas responsible. Indeed, the Srirangam temple, where the Muslim princess Thulukka Nachiyar was later worshipped, was quite pleased to accept gifts from Hoysala Vishnuvardhana’s descendants.

When there is continuing evidence of Muslims being integral to local traditions and economies, why are occasional attacks on elite institutions considered the only metric by which we can gauge religious interactions in the diverse world of medieval India? Most of our ancestors were not conquering kings but rather the humble peoples who came up with such accommodations. Instead of appreciating the diversity of their legacies, it is absurd that we insist on imagining into existence grievances that our ancestors did not hold.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a writer and digital public humanities scholar. He is author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)